Newswise — Chula researchers have revealed the impacts of the coronavirus outbreaks on personal data protection and confidence in the government, which resulted in the concealment of information by infected people, that hindered the mitigation of the pandemic. The governments must educate the public and create awareness of people’s legal rights.

In early 2020, after the government had enacted the Communication Diseases Act, B.E. 2558 (2015), all travelers entering Thailand were required to complete a 14-day quarantine at government-designated Alternative State Quarantine (ASQ) facilities. At that time, some flights were bringing Thai citizens home. The passengers onboard had not been informed of the announcement, and as soon as the planes landed, chaos erupted at the airport. Government officials claimed the authority of the announcement and the law and took all the passengers straight to the quarantine facilities. Of course, many passengers did not agree and immediately fled.

Personal information: names, surnames, and addresses of the passengers of those flights were leaked on social media. These passengers and their families were stigmatized by society as “selfish”, “unpatriotic”, and some were even terrorized in their places.

What does this occurrence say about government officials responsible for protecting public interests vs. the people who are entitled to that protection? In such circumstances, the citizens and governments of many developing countries are often faced with a dilemma between public interests and respect for the citizens’ privacy.

This issue motivated Prof. Dr. Pirongrong Ramasoota, professor of Journalism, the Faculty of Communication Arts, Chulalongkorn University, and a senior research fellow at LIRNEasia to conduct research entitled Health-Related Information & COVID-19: A Study of Sri Lanka and Thailand, in collaboration with Arthit Suriyawongkul, Ramathi Bandaranayake and Ashwini Natesan. The research focuses on the collection, use, and protection of personal data of COVID-19 patients in Thailand, and Sri Lanka. It is a pilot study in the protection of rights, and privacy on personal health data in Information Communication Technology (ICT) in developing countries.

Prof. Dr. Pirongrong Ramasoota

Policy, Law, and Enforcement

Professor Dr. Pirongrong pointed out that, “neither Sri Lanka nor Thailand has any laws to protect personal data. This is partly due to the COVID-19 pandemic in which the governments need to gain access to the personal data of the citizens to assess the situations and mitigate the outbreaks as much as possible. So, the protection of the data needed to be relaxed.”

In January 2020, Thailand detected its first cases and subsequently established the Center for COVID-19 Situation Administration (CCSA) to control the situation under The Communication Diseases Act, B.E.2558 (2015), in conjunction with The Emergency Decree on Public Administration in Emergency Situation, B.E. 2548 (2005) (effective March 26, 2020). Prof. Dr. Pirongrong mentioned that, according to global practices, the Thai government should have also enforced the Personal Data Protection Act (PDPA) to ensure that the collection of personal data remain transparent and systematic.

Unfortunately, this was not the case for Thailand. The enforcement of PDPA was postponed until May 31, 2022, resulting in patients’ data being collected primarily under the guidelines set by The National Health Act, B.E. 2550 (2007), and The Official Information Act, B.E. 2540 (1997). Conversely, the government of Sri Lanka used the Quarantine and Prevention of Disease Ordinance of 1897 (Quarantine Act) to quarantine high-risk people and isolate them from society, along with curfews.

“Sri Lanka has not officially passed the Personal Data Protection Bill. Therefore, the collection of public health data during the outbreaks did not specify the responsibilities of the data controller, nor those of the data processor. Sri Lanka has only used the National Policy on Health Information (2017) as guidelines for the collection, usage, and transfer of personal data of the patients and high-risk groups. The National Digital Health Guidelines and Standards (NDHGS) were also used to govern state and private health institutions, in the areas of health applications management, healthcare networks, emails, websites, protection of privacy, online security, and ethics in public health to ensure that personal information will not be disclosed without written consent by each individual,” said Professor Dr. Pirongrong.

Online platforms linking local networks of worker ants

Prof. Dr. Pirongrong concluded that both Thailand and Sri Lanka used two similar data collection modes:

- The “Paper-based” contact tracing relies on field visits to interview, and collect the data from patients, high-risk groups, and those under quarantine who are asked to fill out forms. Data was later entered into the computer system.

- The “Digital” contact tracing uses applications and database technologies with the following characteristics

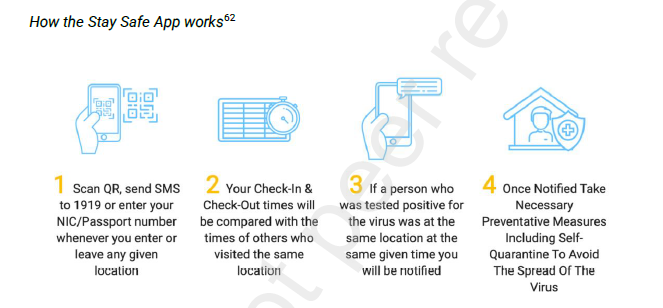

- The Development of specific applications for data collection. For example, Thailand uses the “Thai Chana” application, while Sri Lanka uses the “Stay Safe”.

- The use of social media applications: LINE in Thailand, and WhatsApp and Viber in Sri Lanka.

- The use of online forms to collect data.

The researchers also noted that “Thailand was very successful in controlling the first wave of outbreaks. An important contributing factor was the network of Village Health Volunteers (VHV) who helped strengthen the community healthcare. They did also have access to the villagers, and recognized the coming and going of people in the community. The networks communicated through “Line groups”, and input the data on online forms. This made it possible to monitor high-risk groups and patients effectively.”

Community outreach through an extensive healthcare network that could reach small communities was the key to acquiring detailed, and usable field data, such as high-risk contacts and patients tracking. In the case of Sri Lanka, cooperation with law enforcement and the military also played a role.

Applications and challenges

Both countries were also faced with challenges in cyber security. Sri Lanka’s Stay Safe application that tracks the data on access to public places still needs to prevent data leaks, especially the information from ID cards. Meanwhile, data protection in Thailand is still incomplete. There is also confusion in the role of the data controller and the data processor, and the developers of the data collection application agreed that the responsible agencies do not understand the principles of the Personal Data Act (PDPA) well enough. This reflects the lack of awareness of individuals’ rights and personal data in Thai society.

Prof. Dr. Pirongrong elaborated on the issue of personal data protection that “Sri Lanka protects personal privacy and identities of COVID-19 patients’ through the use of WhatsApp and Viber apps, which are closed groups, while Thailand uses authorized officers to control password during the transmission of personal information. Though no specific duration of patients’ data storage is mandated (international regulations call for the stored data to be destroyed within 60 days). Thai Chana and Stay Safe applications specify 60 days of data retention according to the privacy policy.

Thai Chana App

Recommendations

From the study, Prof. Dr. Pirongrong suggests that “the state should create a clear policy framework on access to personal data, the type of data to be stored, the process of data collection and storage, people who can access the data, and how would the data be used, accountability in case of violation, order of access to the data, and the period of use and destruction of the data. This is for transparency and trust between data users, data owners, and society. If accomplished, these measures will help reduce people’s unwillingness to disclose personal data, or concealment of the information caused by lack of confidence in the system, and fear of being stigmatized by society should their information be leaked.

“Moreover, the governments should get a move on building awareness, knowledge, and understanding on PDPA for the public, private and government sectors, so that they realize their roles and personal rights and their duties to the society,” concluded Prof. Dr. Pirongrong.

To explore the Health-Related Information & COVID-19: A Study of Sri Lanka and Thailand click