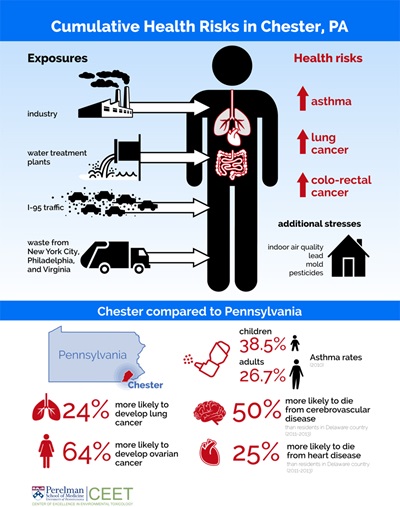

Newswise — “Are you unhappy with your environment?” asked the flyer for a Town Hall meeting at the Faith Temple Holy Church in Chester, PA held earlier this month. More than 75 residents gathered for a Q&A with environmental scientists along with Rev. Horace Stand, pastor of Faith Temple and founder of the Chester Environmental Partnership (CEP), and long-time Chester residents Dolores and John Shelton, also CEP members. Chester has seen its share of hazardous and municipal-waste treatment facilities, including a power plant, refinery, chemical and paper manufacturers, and at least one Superfund site (toxic dump sites that the EPA has designated for clean-up).

“Our environment is our health,” said Linda Birnbaum, PhD, director of the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS) and the National Toxicology Program, who joined other environmental toxicology experts for a panel discussion with attendees. “We’re here to listen to you.”

“What can we do together?” Trevor Penning, PhD, director of Penn's Center of Excellence in Environmental Toxicology (CEET), asked of the residents, referring to other CEET community-based programs focused on issues like asbestos in Ambler and landfills in Eastwick. In answer to questions about funding for Chester, Marilyn Howarth, MD, director of the Community Outreach and Engagement Core for CEET suggested NIEHS’s Research to Action grant program, which brings together community members and environmental and occupational health experts to investigate potential health risks from environmental exposures.

For investigators like Howarth, Penning, and fellow panelist Rich Pepino, deputy director of the Community Outreach and Engagement Core, public health concerns of Philadelphia-area communities drive their research. Whether it’s increased lead levels in Lancaster County children, skyrocketing cases of pediatric asthma in West Philly or an arm’s-length-list of health disparities in the neighborhoods of Chester, CEET investigators take into account a community’s lifetime exposure to environmental toxicants. “This panel’s goal is science in the service of people,” said Howarth.

Working to educate citizens about these health issues is an important aspect of the environmental justice movement. Common chemicals like BPA, which is used in many plastic products and is part of a class of toxicants called estrogen disruptors that mimic estrogen in the body, have been the topic of news stories both locally and across the nation. (Toxicants are toxic substances such as pesticides as opposed to naturally occurring poisons.)

Last year CEET Deputy Director Rebecca Simmons, MD, spoke with the Philadelphia Inquirer about the endocrine-disrupting properties of BPA and increasing alarm over its connection to a myriad of health problems. “I think that the data are unequivocal that endocrine-disrupting chemicals cause problems in animals,” said Simmons in the article. “We see fish in rivers with high levels of endocrine-disrupting chemicals, and the fish are abnormal in terms of their reproductive tracts. Those sorts of animal studies, combined with epidemiology studies, make us very worried.”

At the annual CEET scientific symposium held earlier the same day as the Town Hall, Simmons, Marisa Bartolomei, PhD, a professor of Cell and Developmental Biology, and Sara Pinney, MD, a pediatric endocrinologist at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia, gave an intertwined session on BPA and its effects on the developing embryo. BPA usurps estrogen’s place in molecular pathways, not without negative effects.

In a mouse model, Simmons found that maternal exposure to BPA alters the function of pancreas beta cells in young males, causing an increase in body weight and blood sugar regulation to go awry. Bartolomei showed that exposure to BPA in the first days to weeks of gestation, also in mice, caused an unequal expression of maternal and paternal versions of the same gene. This result caused bones in male mice to become weak and less robust and for some first generation males to take on the rodent version of depression.

To bring it all together, Pinney discussed her in utero exposure studies in humans, the first to look at the association of low-level BPA measurements in amniotic fluid and birth weight. Her team used cells and amniotic fluid from a repository from moms-to-be who had amniocentesis procedures at Penn 10 to 15 years ago. BPA exposure is ubiquitous in the environment due to widespread use in the US. For example, population studies from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey report detectable levels of BPA in over 90 percent of urine samples they analyzed from 2003 to 2004. In a group of amniotic fluid samples from the repository, Pinney found that 40 percent had measurable levels of BPA. In addition, she found that low levels of BPA in mid-gestation amniotic fluid was associated with decreased birth weight, although other studies measuring BPA in maternal urine or serum report inconsistent effects on birth weight. Pinney also observed that male babies exposed to BPA had different genetic marks governing gene expression in their fetal stem cells compared to unexposed babies.

“Our studies do support the findings in the animal models, but more studies are needed to fully understand the full effect of low levels of BPA exposure on the developing fetus,” Pinney said. “Even though many products are now marketed as BPA free, typically BPA has been substituted by very similar compounds, with very similar chemical structures, so we are suspicious that these substitutes will also have similar effects.”

Pinney’s work was a smooth segue to another theme of the day: Taking into account that environmental toxicants not only cause mutations in genes, they also can produce a heritable change without direct damage to DNA. For example, symposium keynote speaker John McLahlan, PhD, chair of Environmental Studies and a professor of Pharmacology at Tulane University, called estrogen disruptors “morphogens,” in that they drive immature cells in very young embryos to mature on an unintended path. Bartolomei says what she sees happening to the mice can be attributed to the fact that BPA causes molecules that control gene expression to fall down on their job in cells of the placenta. This newish field is called environmental epigenetics, the study of changes caused by environmental toxicants that modify which genes make proteins rather than direct mutations in the DNA itself.

In a fairly new area of environmental health, Nate Snyder, PhD, MPH, an assistant professor at the Drexel Autism Institute and an adjunct member of CEET, related autism spectrum disorder (ASD), which is now believed to have a prenatal origin, to exposure to environmental agents. His aim is to identify “modifiable risk factors,” to reduce incidence and severity of ASD, as well as find biomarkers that could help with early screening. Think folic acid and spina bifuda: It’s well-known that taking a folic acid supplement is important for the healthy development of baby, and without it, the risk of spina bifida is increased.

McLahlan called environmental health a transgenerational issue with research and activism playing out in the post-industrial towns in Pennsylvania with Superfund sites. “We need the ability for scientists and health department officials to get the funding to deal with the problems that have existed for years,” said Rev. Strand in a Delaware County Daily Times article the day after the Town Hall, which emphasized the need for uninterrupted capital to allow people of all ages to live in a clean environment.

As one might expect of grandparents who have the perspective of time, the Sheltons emphasized their city’s legacy to its next generations. “We’re here because it’s important that the young folk understand where we’ve been,” said Mr. Shelton.

“We want to make sure our youngsters have a clean place to grow up in,” said Mrs. Shelton, who has lived in Chester since before the start of WWII. “We just need to stay on task.”