Newswise — Testing wastewater to assess the spread of the COVID-19 virus became common and well-publicized during the pandemic, but it has been focused mostly on urban areas.

The Appalachian Regional Commission (ARC) has awarded $400,000 to Virginia Tech, with an additional $50,000 to Virginia Tech from the Virginia Department of Health, for a two-year project to identify and implement improved and new methods to detect pathogens for multiple diseases in the wastewater of rural communities.

“My work and research have primarily been focused on rural areas, and prior to the pandemic, most of my research was on drinking water and health-related challenges,” said Alasdair Cohen, assistant professor of environmental epidemiology in the Department of Population Health Sciences at the Virginia-Maryland College of Veterinary Medicine.

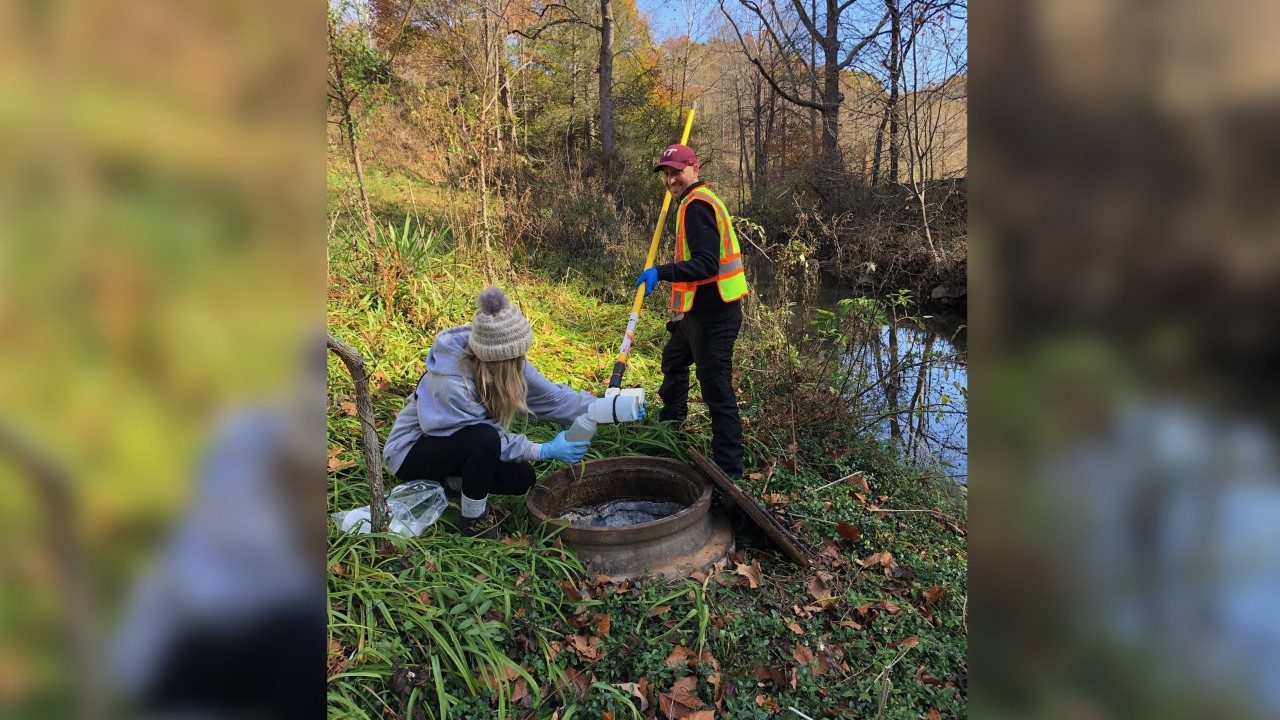

Cohen is the principal investigator on this new project that will build on research Cohen’s team has been conducting since 2022 in collaboration with a wastewater utility in Southwest Virginia and led by Amanda Darling, a Ph.D. student in Cohen’s group.

“Dr. Cohen does important work on drinking water and health, locally and globally,” said Laura Hungerford, head of the Department of Population Health Sciences. “During COVID, he jumped in to help develop improved methods for wastewater surveillance. This let the university and Virginia better track and manage diseases. With ARC funding, he and his community partners will bring this science to benefit rural communities.”

Early in the pandemic, Virginia Tech researchers in the College of Engineering began testing campus wastewater for COVID-19. Cohen was part of this team and led the statistical analyses of the data, finding that they were able to predict future COVID-19 cases at scales as small as one residence hall. The team published its findings in the journal Environmental Science and Technology Water, and this campuswide research collaboration also piqued Cohen’s interest in the use of wastewater surveillance in rural settings.

He is joined in the ARC grant by two co-investigators from the Charles E. Via, Jr. Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering in the College of Engineering: Amy Pruden, University Distinguished Professor in Civil and Environmental Engineering, and Peter Vikesland, the Nick Prillaman Professor in civil and environmental engineering, as well as Leigh-Anne Krometis, associate professor of biological systems engineering in the College of Agriculture and Life Sciences.

Concurrent with the grant funding, Cohen’s team recently published “Making Waves: The Benefits and Challenges of Responsibly Implementing Wastewater-based Surveillance for Rural Communities” in the journal Water Research. The article calls attention to the potential public health benefits of wastewater surveillance for rural communities and to methodological and ethical challenges that Cohen and his colleagues are working to address.

“ARC’s grant of $400,000 will help Virginia Tech expand their work to detect pathogens in wastewater from rural communities,” U.S Rep. Morgan Griffith said in a press release announcing the grant. “This work is aimed at improving our country’s public health through better community health monitoring and outbreak forecasting.”

The Virginia Department of Health (VDH) monitors wastewater at sites across the commonwealth for pathogens causing COVID-19, influenza A, influenza B, hepatitis A and respiratory syncytial virus. The department found though that results from some smaller rural communities are challenging to interpret.

“This project aims to complement VDH's efforts in using wastewater-based surveillance to advance public health in rural towns in Appalachian Virginia,” said Rekha Singh, the department's Wastewater Surveillance Program manager. “The VDH has initiated wastewater surveillance for COVID-19 in communities statewide since September 2021. This new project will help identify the best practices for sampling in small communities and will assist VDH in implementing effective wastewater surveillance in similar communities.”

Infrastructure is often part of the challenge in testing rural wastewater, Cohen said.

“You have fewer people but over a larger space, so you have more wastewater collection infrastructure per person than you would in an urban setting,” Cohen said. “Many rural towns, and especially older rural towns, are going to have sewage collection infrastructure with a lot of breaks and cracks in the pipes. That means sewage could get out into the ground and it means water can get into the pipes.”

Especially after periods of heavier rain, runoff seeping into sewage systems could dilute the results of wastewater testing in rural areas. It can also mean tax dollars down the drain with sewage plants treating rainwater alongside wastewater.

“We have enough preliminary data from our pilot research to show that this can be a problem,” Cohen said.

The grant will allow Cohen’s team to take on wastewater surveillance in new Southwest Virginia communities, gaining efficiency as experiences from prior studies are applied.

“The goal is we want to try to develop an approach so that rural utilities and public health agencies can determine if wastewater surveillance is something that makes sense for a given rural community,” Cohen said. “And if so, how could it best be implemented?”